Mumbai: Even as streaming platforms proliferate, India remains a cinema-first market at heart. Eight out of ten Indian moviegoers still prefer watching films in theatres over OTT, drawn by the immersive sound, superior picture quality and the social experience of “going out” to watch a movie. Yet the business of theatrical exhibition is shrinking — and the gap between audience appetite and industry performance is widening.

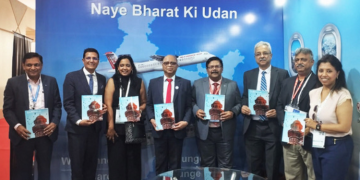

That is the central paradox highlighted in “The Story of Film Exhibition in India”, a new report prepared by EY and released by The Multiplex Association of India (MAI), the apex body representing multiplex exhibitors across the country. The study lays out how India’s cinema infrastructure has failed to keep pace with its population and economic growth, and why regulatory and commercial reform is now critical to revive theatrical exhibition.

A nation that loves cinemas — but can’t access them

The report shows that while 81% of surveyed cinemagoers prefer theatres over streaming, India’s cinema footprint remains extremely thin. Out of a population of 1.4 billion, only around 150 million people — about 10% — attend theatres in a year, according to industry estimates. The country currently has just 9,927 screens, spread across about 3,150 pin codes, while 16,350 pin codes have no cinema screens at all.

This under-penetration is one of the biggest brakes on growth. MAI estimates that if India were to double its screen count to around 20,000 over the next five years, theatrical revenues could rise by ₹6,600 crore, while generating 1.25 lakh direct jobs and ₹950 crore in additional tax revenue for governments.

Revenues and footfalls have slid since 2019

Despite India’s broader economic growth, theatrical exhibition has been moving in the opposite direction. Between 2019 and 2024, total filmed entertainment revenues fell 2%, from ₹19,100 crore to ₹18,746 crore. Revenue per screen declined from ₹1.21 crore to ₹1.15 crore over the same period.

Footfalls paint a starker picture. Annual theatre attendance dropped from 1.46 billion in 2019 to 0.86 billion in 2024, a 41% decline. Average footfalls per screen fell 44%, reflecting not just fewer releases that work, but fewer people showing up.

The success rate of films has also weakened. The number of movies crossing ₹100 crore at the box office fell from 17 in 2019 to 10 in 2024, even though roughly the same number of films were released in theatres.

Content and windows are hurting cinemas

According to the MAI–EY study, the biggest deterrent is not ticket prices — it is content and release strategy.

-

55% of cinemagoers say the quality of films is their main concern.

-

78% of producers point to a shortage of quality writers and stories.

-

70% of audiences want better storytelling, music and visual effects.

At the same time, the traditional 90-day theatrical window before OTT release has collapsed to just four to eight weeks. As a result, 53% of viewers said they waited for at least one film to appear on streaming instead of watching it in theatres in the last three months. One in three openly admits they will wait if the OTT window is short.

This shift is also fuelling piracy. 51% of media consumers access pirated content, with 76% of them in the 19–34 age group. Once a film hits digital platforms, illegal copies spread rapidly, eroding box-office potential.

India’s pricing disadvantage

India’s low per-capita income further constrains pricing power. Although it is the world’s fifth-largest economy, India ranks 140th in GDP per capita, with a 70% income gap between rural and urban households. That forces cinemas to keep ticket prices low: India’s average ticket price is just ₹134, and even the country’s largest multiplex chain averages ₹259 per ticket — far below global benchmarks on a purchasing-power basis.

Food and beverage revenue also lags international markets. Indian moviegoers spend 54% of ticket value on snacks, compared with up to 72% in developed markets, limiting exhibitors’ ability to offset low ticket prices.

The policy reset MAI is seeking

To unlock growth, MAI argues that exhibition needs to be treated like a modern service business, not a heavily regulated utility.

Among its urgent recommendations:

-

Restore clearer and longer theatrical windows, especially for successful films, to rebuild exclusivity and reduce piracy.

-

Deregulate ticket pricing, allowing cinemas to price dynamically like hotels or airlines.

-

Allow theatres to operate as multi-use venues, hosting live sports, concerts, corporate events, birthdays, prayer meets and MICE activities during non-prime hours.

-

Permit 24×7 cinema operations nationwide, following Maharashtra’s 2020 precedent.

-

Enable faster, self-declared ticket price changes instead of prior government approvals.

-

Create censorship and rating parity with OTT platforms, given theatres’ controlled and limited reach.

For the long term, MAI wants the government to actively back screen expansion through tax holidays for new cinemas in underserved pin codes, single-window clearances, easier land access for low-cost theatres, and simpler FDI norms for cinema infrastructure. It also proposes “entertainment-in-a-box” models — mobile or temporary cinemas that can move across towns.

A last-mile cultural infrastructure

The report positions cinemas not just as entertainment outlets, but as last-mile cultural infrastructure that anchors India’s film economy. With strong audience preference still intact, MAI believes the decline of theatrical exhibition is not inevitable — it is a policy and structural problem waiting to be fixed.

If India can align regulation, content economics and infrastructure, the country’s love for the big screen could once again translate into sustainable growth — not just for exhibitors, but for the entire film ecosystem.